Chapter 12: The Knowledge Spiral

Working with AI doesn't just teach you new things. It reveals how much of what you 'know' is shallow, contextual, or simply wrong. And it happens at a pace that's psychologically disorienting.

Chapter 12: The Knowledge Spiral

"A new tool does not solve all problems; it merely frees us to concentrate on other ones." - Alan J. Perlis

The Day I Discovered I Was Wrong About Everything

You think you know something. Then you ask AI for help, and it casually corrects an assumption you've held for years.

Your first instinct is: no, the AI is wrong. You check the documentation. And then you realize: you've been working with an outdated mental model, one that was "good enough" in practice but technically incorrect.

This keeps happening. Not occasionally, but constantly.

The framework you thought you understood has edge cases you never encountered. The pattern you thought was optimal has better alternatives you never learned about. The architecture you thought was standard practice has evolved while you kept building with the old version.

Working with AI doesn't just teach you new things. It reveals how much of what you "know" is shallow, contextual, or simply wrong. And it happens at a pace that's psychologically disorienting.

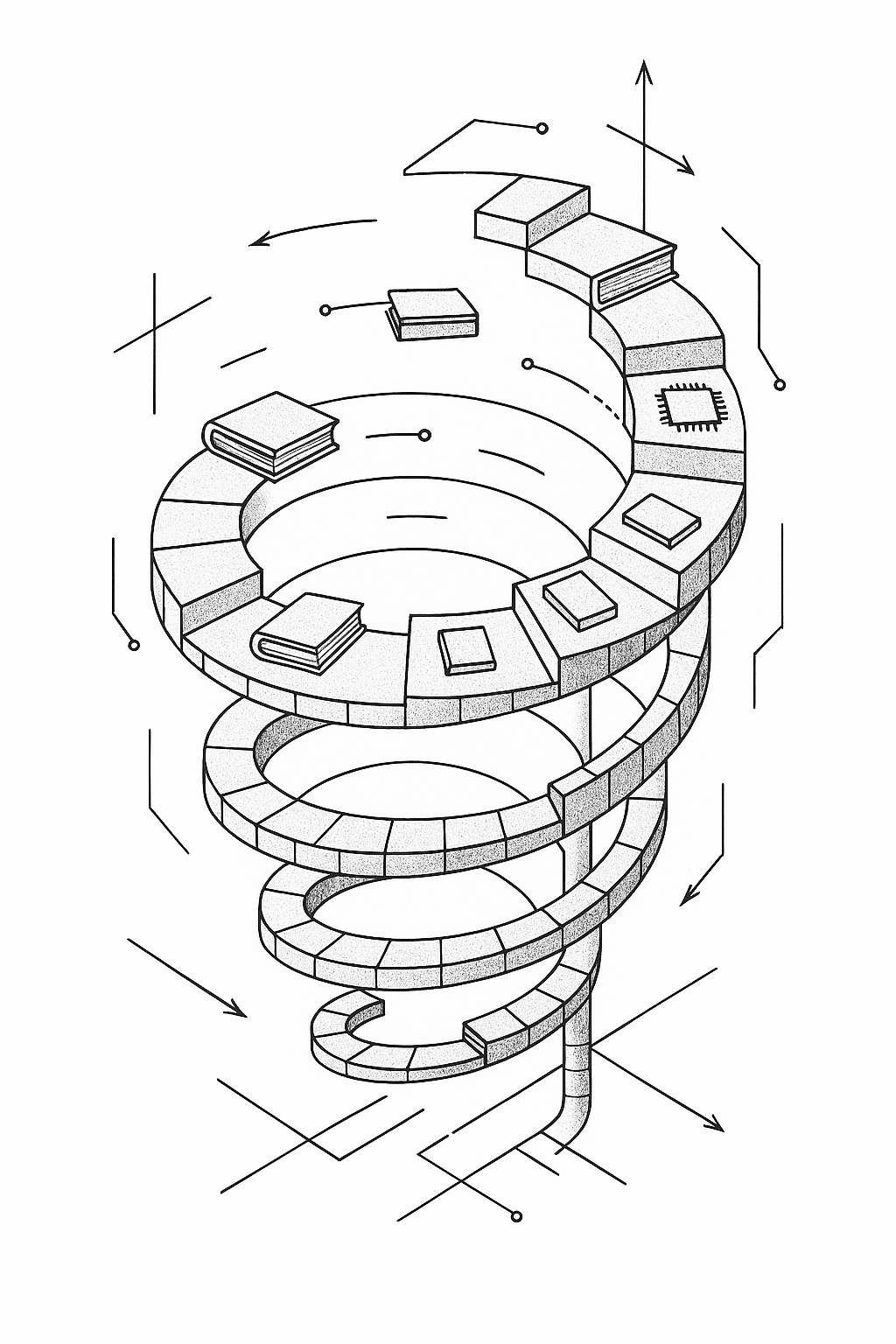

This chapter explores the spiral of knowledge that emerges when you learn with artificial intelligence. Not just the acceleration of acquiring new information, but the fundamental transformation of how knowledge itself works when intelligence becomes distributed between human and machine minds.

The Unlearning Acceleration

Working with AI doesn't just accelerate learning. It accelerates unlearning.

The painful but necessary process of discovering that things you thought you knew were incomplete, outdated, or wrong. This unlearning happens at a pace that can be psychologically disorienting.

In traditional learning, you discover gaps in your knowledge gradually.

A conference talk reveals a technique you hadn't considered. A code review exposes a pattern you'd missed. A production bug teaches you about an edge case you'd overlooked. These moments of learning are spaced out over months or years, giving you time to integrate new understanding with existing knowledge.

AI collaboration compresses this process dramatically.

In a single afternoon working with Claude on a Neo4j integration for my blog, I discovered that my understanding of graph database indexing was superficial, my approach to Cypher query optimization was inefficient, and my mental model of relationship traversal performance was based on assumptions from relational databases that simply didn't apply.

This wasn't just learning new information. It was the uncomfortable realization that my existing expertise was built on shaky foundations.

The AI didn't just fill gaps in my knowledge; it revealed the gaps I didn't know existed.

The velocity of this unlearning creates a peculiar psychological state.

Traditional expertise brings confidence. You know what you know, and you know what you don't know.

But AI-assisted learning reveals a third category: things you thought you knew but didn't. This category grows faster than your traditional knowledge, creating a kind of epistemic vertigo.

The Metacognitive Mirror

AI serves as an unexpected mirror for your own thinking processes. When you explain problems to an AI, when you provide context and clarify requirements, when you evaluate and refine AI suggestions, you're forced to examine your own mental models with unusual clarity.

Traditional programming is often intuitive. You "know" the right approach without fully articulating why. You follow patterns that feel correct, make architectural decisions based on experience, debug issues through intuitive leaps. This intuitive programming works well, but it makes your knowledge tacit, difficult to examine or improve.

AI collaboration makes the tacit explicit. To get good results from an AI, you have to articulate not just what you want but why you want it. You have to explain constraints you usually take for granted, make explicit the trade-offs you typically navigate unconsciously, surface the assumptions that normally remain buried in your implementation choices.

This externalization of thought reveals patterns in your own thinking that you might never have noticed otherwise. I discovered through months of AI conversations that I have a strong bias toward stateless architectures, that I consistently underestimate the importance of error handling in initial implementations, that I tend to optimize for developer experience over runtime performance.

These insights weren't available through traditional self-reflection or even through working with human colleagues. The AI's need for explicit context forced a level of self-examination that normal programming work doesn't require.

The Distributed Expertise Model

Working with AI has fundamentally changed how I think about expertise. Traditional expertise is localized in individual minds, accumulated through years of experience, and demonstrated through the ability to solve problems independently. AI collaboration suggests a different model: distributed expertise that exists in the connections between human knowledge, artificial intelligence, and the dynamic interaction patterns that emerge from their combination.

I no longer think of myself as having expertise in AWS CDK. Instead, I have expertise in the collaborative process of using AI to solve AWS infrastructure problems. My knowledge includes not just CDK patterns and best practices, but also which types of infrastructure questions work well with AI assistance, how to structure context for complex deployment scenarios, and when to trust AI-generated CloudFormation versus when to verify manually.

This distributed model changes what expertise means. It's not just what you know, but how effectively you can orchestrate the combination of human insight and AI capability. It's not just about having answers, but about knowing how to ask questions that generate better answers from the human-AI system.

The transition can be unsettling. Traditional expertise provides a clear sense of professional identity and value. Distributed expertise is more ambiguous. Are you an expert, or are you just good at working with an expert system? Does the distinction matter if the outcomes are superior?

The Collaborative Knowledge Creation

Something remarkable happens in the space between human knowledge and AI capability: new knowledge gets created that neither party possessed independently. This isn't just information synthesis or pattern matching. It's genuine knowledge creation through the collision of different types of intelligence.

You describe a problem in your domain. The AI recognizes patterns from entirely different fields. Suddenly there's a connection you never would have made - not because you're not smart enough, but because the domains were too distant in your mental map. The AI doesn't "know" your problem space like you do, but it can bridge conceptual gaps that would take years of cross-disciplinary study to discover on your own.

Here's the fascinating part: neither party had the complete idea independently. It was created in the collaborative space between human context and AI pattern recognition. When you trace back where these ideas come from, there's no clear lineage - they emerge from the interaction itself.

This collaborative knowledge creation happens regularly in AI-assisted development, but it's easy to miss because we're trained to think in terms of human ideas versus AI suggestions. The reality is more complex: many of the best solutions emerge from the intersection of human domain knowledge and AI pattern recognition, from the creative tension between human intuition and artificial analysis.

Recognizing this collaborative creation changes how you approach AI partnerships. Instead of just seeking answers to predetermined questions, you start exploring the emergent space where new ideas form.

The Paradox of Infinite Information

AI provides access to vast amounts of information, but this abundance creates its own challenges. When you can get detailed explanations of any technical concept, comprehensive code examples for any pattern, and thorough analysis of any architectural decision, the bottleneck shifts from access to information to the ability to evaluate and integrate that information meaningfully.

This paradox became clear to me while building the Python ETL pipeline for my blog's content processing. I could ask Sonnet 4 about any aspect of data transformation, streaming architectures, error handling patterns, performance optimization techniques. Within minutes, I had access to more information about ETL best practices than I could absorb in weeks of traditional research.

But having access to all this information didn't automatically make me better at building ETL pipelines. In fact, it sometimes made decision-making more difficult. When you know about twelve different approaches to data validation, how do you choose the right one for your specific context? When you understand the theoretical trade-offs of various streaming architectures, how do you make practical decisions about what to implement?

The skill that becomes critical in this environment isn't information gathering, it's information filtering. Learning to ask the right questions, recognize relevant patterns, and synthesize scattered insights into actionable understanding. The AI can provide the information, but the human has to provide the judgment about what information matters.

The Temporal Collapse of Learning

AI assistance creates a strange temporal effect where learning that would traditionally unfold over months or years gets compressed into hours or days. This compression isn't just about speed; it's about the fundamental nature of how understanding develops.

Traditional learning follows a predictable pattern: initial exposure, confusion, gradual understanding, practice, mastery. Each phase takes time, allowing concepts to settle, connections to form, and understanding to deepen through experience. The temporal spacing is crucial for real learning.

AI-assisted learning can short-circuit this process. You can go from knowing nothing about a technology to implementing complex solutions using that technology in a single session. But this compression comes with costs. The understanding might be functional but shallow. You can implement the solution without really understanding why it works.

I experienced this while exploring graph databases for my blog's content relationships. Within two hours of working with Claude, I had implemented a complete Neo4j integration with sophisticated queries, proper indexing, and optimized traversal patterns. But when a colleague asked me to explain why I'd chosen certain relationship modeling approaches, I realized my understanding was largely procedural. I knew what to do, but not always why.

This temporal collapse of learning creates new categories of knowledge: functional understanding that enables implementation without deep comprehension, pattern recognition that works in similar contexts but doesn't transfer to different problems, and theoretical knowledge that covers many details but lacks the experiential grounding that comes from struggling with real-world complexity.

The challenge is developing strategies for converting this compressed learning into genuine understanding.

The Question-Answer Inversion

Traditional learning starts with questions and seeks answers. You identify something you don't know and then look for resources that provide that information. The learning path is question-driven: you know what you want to learn and you pursue targeted knowledge acquisition.

AI collaboration inverts this relationship. Often, the most valuable learning comes not from answers to your questions, but from questions you wouldn't have thought to ask. The AI, drawing from patterns across vast training data, can identify relevant questions that your limited experience wouldn't have generated.

This became evident while working on authentication patterns for a client project. I asked Sonnet 4 about implementing OAuth2 flows, expecting straightforward implementation guidance. Instead, the AI started by questioning my assumptions: "Are you handling token refresh properly for long-lived sessions? Have you considered the implications of token storage in different browser environments? What's your strategy for graceful degradation when auth services are unavailable?"

These weren't questions I had thought to ask, but they were crucial questions for building robust authentication systems. The AI's questions revealed blind spots in my thinking, highlighted edge cases I would have discovered painfully in production, and guided me toward more sophisticated solutions.

This question-answer inversion changes the learning dynamic. Instead of seeking answers, you're seeking better questions. Instead of filling known knowledge gaps, you're discovering unknown knowledge gaps. The AI becomes not just a source of information but a generator of inquiry.

The skill that becomes crucial is learning to follow these AI-generated questions, to let your learning path be guided by discoveries you couldn't have anticipated. This requires a different kind of intellectual humility: not just admitting what you don't know, but being open to discovering that you don't know what you don't know.

The Empathetic Algorithm

One of the most surprising aspects of working closely with AI is how it develops what feels like empathy for your thinking patterns. Not emotional empathy, but something more like cognitive empathy: an understanding of how you process information, what kinds of explanations resonate with you, what level of detail you need for different types of problems.

This cognitive empathy emerges gradually through repeated interactions. Early in my relationship with Claude, explanations often felt generic, technically correct but not quite tuned to my learning style. Over time, as I provided feedback and asked follow-up questions, the AI began adapting its communication patterns to match my needs.

When I ask about architectural patterns now, Claude doesn't just provide abstract descriptions. It gives concrete examples using technologies I work with, relates new patterns to ones I already understand, and anticipates the types of trade-offs I typically care about. When I'm debugging complex issues, it structures its analysis in ways that match my diagnostic thinking patterns.

This adaptation isn't just convenient; it's epistemologically fascinating. The AI is learning not just what I know, but how I learn. It's developing a model of my cognitive preferences and using that model to optimize knowledge transfer. In a sense, it's learning to teach me in the way I learn best.

But this empathetic adaptation raises interesting questions about the nature of knowledge and learning. When an AI adapts its explanations to your cognitive style, are you learning the subject matter or are you learning the AI's model of the subject matter as filtered through its model of your thinking? The boundary becomes unclear, and perhaps that's the point.

The Meta-Learning Acceleration

Perhaps the most profound change that AI introduces to learning is meta-learning: learning how to learn more effectively. When you work with AI regularly, you develop not just domain knowledge but knowledge about the learning process itself. You learn how to ask better questions, structure problems more effectively, recognize patterns across different domains, and transfer insights between contexts.

This meta-learning acceleration compounds over time. Each AI interaction teaches you something about the subject matter, but also something about how to collaborate with AI more effectively. You learn which types of questions generate the most useful responses, how to provide context that leads to better solutions, and when to trust AI suggestions versus when to verify independently.

But the meta-learning goes deeper than just improving AI collaboration skills. Working with AI exposes you to such a wide variety of problems and solutions that you start recognizing abstract patterns that transcend specific technologies or domains. You develop better intuition for what makes a solution elegant, what kinds of architectures are likely to be maintainable, and what types of trade-offs are worth making in different contexts.

This pattern recognition ability transfers back to purely human contexts. After months of AI-assisted development, I found myself better at code reviews, architecture discussions, and technical mentoring. The AI collaboration had improved not just my ability to work with AI, but my ability to think about technical problems generally.

The acceleration comes from the sheer volume of learning interactions. Where traditional learning might involve deep engagement with a few problems over long periods, AI-assisted learning involves broad engagement with many problems over short periods. The breadth creates opportunities for pattern recognition that depth alone cannot provide.

The Wisdom Paradox

As access to information becomes unlimited and analysis becomes instant, the scarcity shifts to wisdom: the ability to know what questions are worth asking, what problems are worth solving, and what knowledge is worth pursuing. AI can provide vast amounts of information and sophisticated analysis, but wisdom requires human judgment about what matters.

This paradox became apparent while building my blog's analytics system. I could ask AI about dozens of different metrics, various analysis techniques, sophisticated data visualization approaches. The AI could explain the technical implementation of any analytics approach I could imagine. But it couldn't tell me which metrics would actually be meaningful for my specific goals, which analyses would provide actionable insights, or how much complexity was worth the analytical capability.

Those decisions required wisdom that comes from understanding not just the technical possibilities but the human context: what I was trying to achieve, what my constraints were, what would actually improve my writing and reader engagement. The AI could provide the how, but I had to provide the why.

This wisdom paradox suggests that the most valuable human skill in an AI-augmented world isn't technical knowledge, which AI can provide or supplement. It's the judgment to know what's worth knowing, what problems are worth solving, and what trade-offs are worth making. These are inherently human questions that require understanding of values, goals, and context that goes beyond pattern matching or information synthesis.

The Future of Knowing

We're approaching a future where the distinction between knowing something and knowing how to find out about something becomes increasingly meaningless. When AI can provide expert-level information about any topic instantly, when analysis can be performed faster than you can formulate questions, when implementation can happen at the speed of thought, what does it mean to "know" something?

This transformation goes beyond just having better tools. It's about the fundamental nature of knowledge and expertise in a world where intelligence is abundant and information is infinite. The skills that matter shift from knowledge retention to knowledge navigation, from individual expertise to collaborative intelligence, from having answers to asking better questions.

But this shift also preserves and amplifies uniquely human capabilities: the ability to recognize what matters, to make value judgments about competing approaches, to understand the human context that gives meaning to technical solutions, to provide the wisdom that guides the application of intelligence.

The future of knowing isn't about humans versus AI or humans replaced by AI. It's about humans and AI, thinking together in ways that neither could achieve alone. The spiral of knowledge continues, but now it includes both human and artificial intelligence, both individual and collective understanding, both what we know and what we can discover together.

And what then? What becomes of learning when intelligence itself becomes fluid, distributed, collaborative? What becomes of expertise when knowledge becomes infinite and analysis becomes instant?

These questions don't have answers yet. But exploring them, thinking through their implications, preparing for their possibilities, that's the real work of learning in the age of artificial intelligence.

Knowledge itself is being transformed by artificial intelligence. Not just how we acquire it, but what it means to know something in a world where intelligence is distributed between human and machine minds. In our next chapter, we'll explore how this transformation of knowledge creates new forms of economic value and changes the fundamental equations of capability and cost.

Sources and Further Reading

The opening quote from Alan J. Perlis reflects the theme of tools as cognitive amplifiers, drawing from his influential work on programming language design and his famous epigrams about computation and human thinking.

The concept of "unlearning acceleration" builds on Thomas Kuhn's work on scientific revolutions and paradigm shifts, though applied to individual learning experiences rather than scientific communities.

The discussion of distributed expertise references Edwin Hutchins' work on "Cognition in the Wild," which examines how knowledge and problem-solving can be distributed across people and tools, extended here to human-AI partnerships.

Epistemic philosophy underlying these discussions draws from Karl Popper's work on the growth of knowledge and the falsification of theories, as well as Donald Schön's concept of reflective practice in professional knowledge.

The temporal aspects of learning discussed here connect to research on expertise development, including the work of K. Anders Ericsson on deliberate practice, though reconsidered in the context of AI-accelerated learning cycles.

Previous Chapter: Chapter 11: The Social Machine

Next Chapter: Chapter 13: The Value Equation