Born to Run by Christopher McDougall: The Book That Changed How We Think About Running

McDougall went to Mexico's Copper Canyons looking for the secret to running without injury. What he found was a hidden tribe of superathletes, an argument that humans evolved to run, and a story so good it launched an entire movement. Born to Run is part investigation, part adventure, and part love letter to the oldest human activity.

The Question That Started Everything

Christopher McDougall had a simple problem: his feet hurt. Every time he ran, something broke down. Doctors told him to stop. His body, they said, was not built for running.

But something about that answer felt wrong. Humans have been running for millions of years. We ran down prey across African savannas before we invented spears. We ran to hunt, to migrate, to survive. How could the bodies that carried us through all of that be fundamentally unsuited to the activity?

McDougall went looking for the answer. He found it in the Copper Canyons of northwestern Mexico, among the Tarahumara people, a tribe whose members routinely run hundreds of miles through brutal terrain in thin sandals. They do not get injured. They do not burn out. They run with an ease and joy that contradicts everything modern sports medicine tells us about the limits of the human body.

Born to Run is the story of that search, and it is one of the best adventure books I have ever read, running or otherwise.

The Tarahumara and What They Teach Us

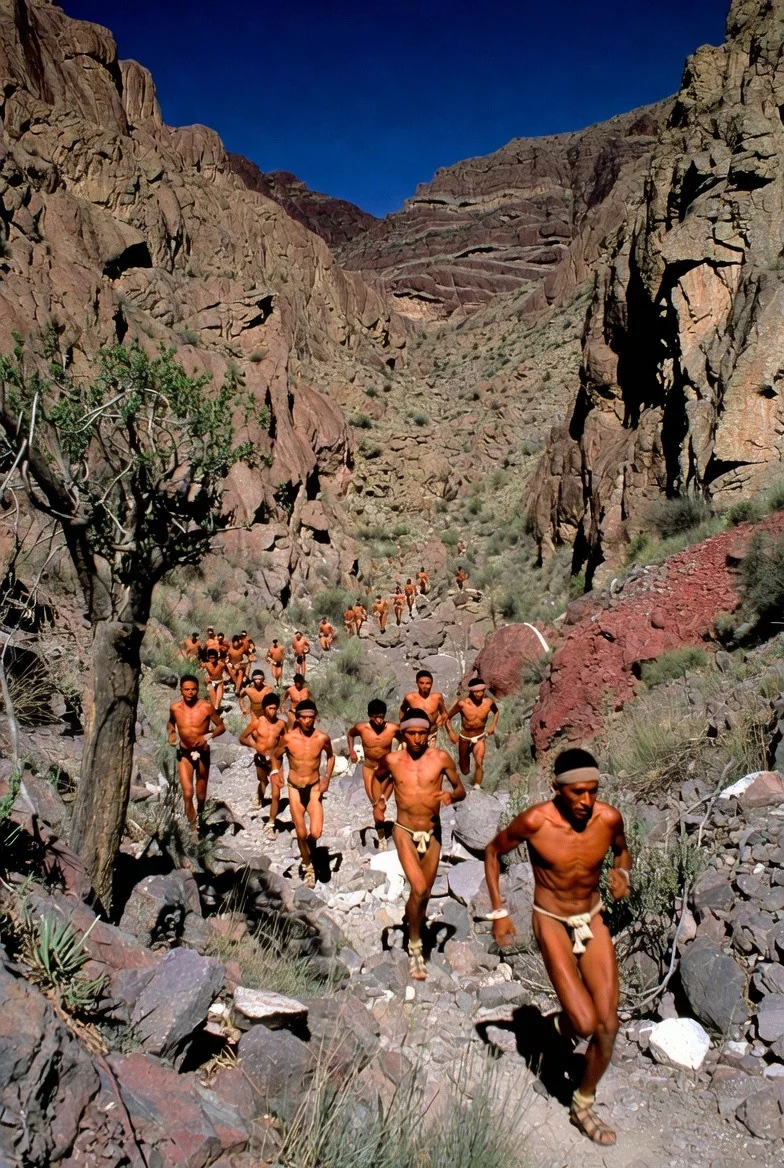

The Tarahumara, who call themselves Raramuri ("the running people"), live in settlements scattered through the deep canyons of the Sierra Madre. Access is difficult. The terrain is punishing. And the Raramuri navigate it by running.

Not jogging. Running. Distances that would qualify as ultramarathons by Western standards, performed as a routine part of daily life. Children run. Elders run. Their competitive races, called rarajipari, can cover 200 miles or more over rough canyon floor, often while kicking a small wooden ball.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Title | Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen |

| Author | Christopher McDougall |

| Publication Year | 2009 |

| Genre | Adventure, Science, Sports, Anthropology |

| Length | ~304 pages |

| Main Themes | Human evolution, endurance running, biomechanics, the barefoot movement, joy of movement |

| Key Concept | Humans evolved as persistence hunters; our bodies are optimized for long-distance running, and modern shoes may cause more injuries than they prevent |

| Who Should Read | Runners of any level, anyone curious about human evolution, people looking for a great adventure story |

They do this in huaraches, thin sandals made from strips of leather or old tire rubber. No cushioning. No arch support. No motion control. Just a flat piece of material between foot and ground.

And they do not get injured.

This observation is the engine of the entire book. How is it possible that a tribe running in sandals stays healthier than Americans spending $100 billion a year on running shoes engineered by the best biomechanics labs in the world?

The Evolutionary Argument

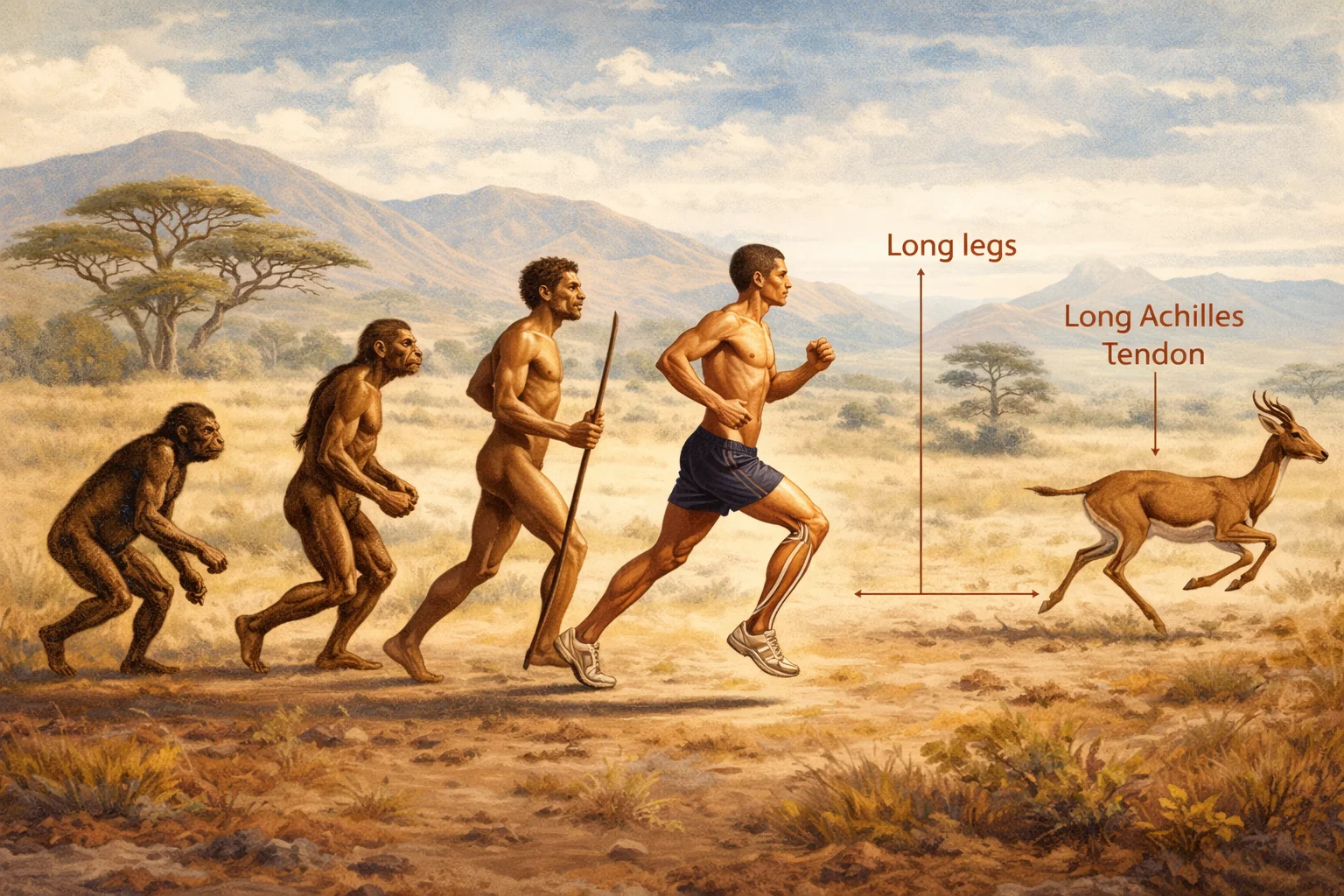

McDougall builds his case around the work of Harvard evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman and his colleague Dennis Bramble. Their research, published in Nature in 2004, argues that humans evolved specifically for endurance running.

The evidence is in our anatomy. Long legs. Short toes. The nuchal ligament at the base of the skull that stabilizes the head during running (not walking; walking does not need it). The Achilles tendon, which stores and releases energy with each stride. Abundant sweat glands that cool us far more efficiently than panting, which is why we can outrun nearly any animal on the planet in sustained heat.

Our ancestors did not need speed. They needed endurance. Persistence hunting, which is still practiced by some indigenous groups, involves chasing prey at a moderate pace until the animal overheats and collapses. No weapons required for the chase itself. Just the ability to keep going after the prey has stopped.

This is what Lieberman and Bramble call "the endurance running hypothesis," and if they are right, it means that running is not something we happen to be able to do. It is what we were built for. It is our evolutionary birthright.

I think about this every time I run on the open BLM land in Nevada. Miles of rolling hills, ancient-looking rocks, and vast openness. The terrain is uneven, the sky is vast, and you are right there with it all. When I am out there, sweating and breathing and covering ground across those Nevada hills, I am doing precisely what my body was designed to do over two million years of evolutionary pressure.

That is not a metaphor. It is biology.

The Shoe Industry Problem

The most controversial argument in the book targets the modern running shoe industry. McDougall makes the case that cushioned, supportive shoes do not prevent injuries. They cause them.

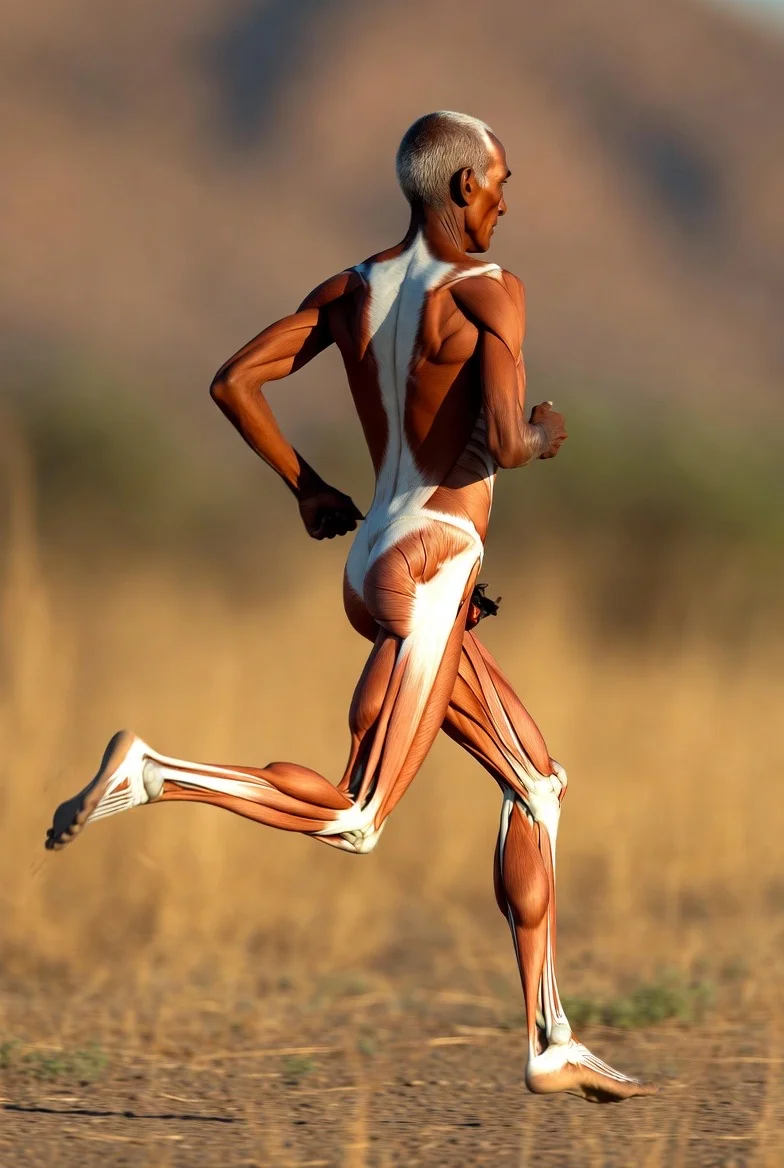

The logic works like this: a cushioned shoe allows you to heel-strike, which is to say, land on your heel with your leg extended in front of you. This sends a shock wave up through the leg with every stride. The shoe absorbs some of that shock, but the fundamental biomechanics remain destructive. Your body cannot feel the impact properly because the shoe muffles the feedback, so you keep running in a way that damages your joints and connective tissue.

Remove the shoe, and the body self-corrects. You cannot heel-strike barefoot on a hard surface without immediate pain. Your body naturally switches to a forefoot or midfoot strike, which uses the foot's arch, the Achilles tendon, and the calf muscles as a natural spring and shock absorber. The system works. It worked for two million years before Nike existed.

This argument sparked the barefoot and minimalist running movement. Vibram FiveFingers, Xero Shoes, and dozens of other brands emerged directly in response to this book. Phil Knight, in Shoe Dog, tells the story of building Nike from the runner's perspective; McDougall tells the story of what the modern shoe industry may have gotten wrong despite billions in research funding.

Having run in both traditional shoes and more minimal footwear, I can say the difference is real. The connection to the ground, the feedback loop between foot and terrain, the way your stride naturally shortens and quickens when there is less material between you and the earth: these are observable, repeatable experiences. Whether the science is fully settled is a separate question. But the lived experience of running closer to the ground is meaningful.

Caballo Blanco and the Cast of Ultrarunners

The human story that propels the book is centered on Micah True, known as Caballo Blanco ("White Horse"), an American who abandoned conventional life to live among the Tarahumara and run their canyons. Caballo is part mystic, part hermit, part ambassador for the Raramuri way of running.

McDougall builds toward a climactic race organized by Caballo: a 50-mile ultramarathon through the Copper Canyons, pitting elite American ultrarunners against Tarahumara runners on their home terrain.

The American cast includes Scott Jurek, one of the greatest ultrarunners in history, who dominated the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run seven consecutive years. And Jenn Shelton and Billy Barnett, young runners of almost reckless talent and enthusiasm.

These are people who run 100 miles through mountains for fun. Not for sponsorships or fame, though some have those. Because they love it. Because the act of running that far strips away everything false and leaves only what is real.

I understand this impulse. Not at the 100-mile level. But the desire to push past the point where the body says stop and find out what is on the other side: that is familiar to every runner who has ever gone further than they planned. There is a moment past exhaustion where the running stops being effort and starts being something else. Something closer to flight. If you have felt it, you know exactly what I mean. If you have not, Born to Run will make you want to.

The Joy of Running

Buried inside the science and the adventure is the book's real thesis, and it is simpler than all the evolutionary biology: running should be joyful.

The Tarahumara do not run grimly. They do not run to lose weight or to train for races or to check boxes on a fitness app. They run because running is woven into their culture, their social life, their spiritual practice. Their races are celebrations. They laugh. They drink corn beer and dance and then run 50 miles through the canyons and laugh some more.

McDougall contrasts this with the Western running experience: expensive shoes, rigid training plans, injury anxiety, performance metrics. We have turned the most natural human activity into a clinical, stressful, often painful chore. And then we wonder why injury rates keep climbing.

"You don't stop running because you get old," McDougall writes, quoting one researcher. "You get old because you stop running."

I think about this every time I see someone grinding through a joyless training run on a treadmill, staring at a screen. Running was never meant to happen indoors under fluorescent lights. It was meant to happen outside, on trails, in sun and wind and rain, with the ground uneven beneath your feet and the sky open above you. The Tarahumara know this. Every runner who has ever felt genuinely alive on a trail knows this.

What the Book Gets Right and Where It Oversimplifies

The evolutionary argument is compelling and well-researched, but the shoe industry critique is more nuanced than the book sometimes acknowledges. Not everyone who switches to barefoot running improves. Some people get injured. Transitioning requires patience and adaptation that many readers skipped in their enthusiasm.

The Tarahumara themselves have faced challenges since the book's publication. Tourism increased. Drug cartels moved into the region. Some Raramuri leaders have spoken publicly about the unwanted attention. McDougall's portrayal, while respectful, inevitably simplified a complex culture.

And Caballo Blanco, the emotional center of the book, died in 2012 during a solo run in the Gila Wilderness of New Mexico. He was 58. The autopsy found an enlarged heart, the organ literally too big from a lifetime of endurance running. The tragedy adds a layer of complexity to the book's celebration of extreme running.

None of this diminishes the core truth: humans are runners. Our bodies evolved for it. The joy of running is not a modern invention or a runner's delusion. It is built into our biology. Born to Run makes that case more persuasively than any book before or since.

Rating and Recommendation

5/5. This is the book I give to people who say they hate running. Not because it will convince them to run. Because it will change how they think about what running is, and what it means that we are the species that does it.

If you are already a runner, this book will deepen your understanding of why you do what you do. The evolutionary science alone is worth the read.

If you love adventure writing, the Copper Canyon narrative is as good as anything by Krakauer or Theroux.

If you are curious about human evolution, biomechanics, or anthropology, the research sections are accessible and well-sourced without being dumbed down.

Read it. Then go outside and run somewhere beautiful.

Buy Born to Run on Amazon (Affiliate Link)

Related Reading: The Running Book Quartet

This review is part of a four-book series exploring different dimensions of running:

Part 1: The Philosophical Runner

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami. Running as meditation, creativity, and self-discovery.

Part 2: The Scientific Adventure (This Post)

Evolutionary running science, the Tarahumara tribe, and the barefoot movement.

Part 3: The Competitive Legend

Pre: Steve Prefontaine's Story by Tom Jordan. Running as art, amateur athletics, and the relentless pursuit of excellence.

Part 4: The Business of Running

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight. How a love of running built one of the most recognizable brands on the planet.

Together, these four books cover the mind (Murakami), body (Born to Run), spirit (Pre), and business (Shoe Dog) of running. Read one or read all four. Each stands on its own, and together they form the best education in the culture, science, and soul of running that I know of.

This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase through these links, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thank you for supporting this blog.